The art of practice

Claire Feldkamp

7/4/2017

“You must forget what you know because what you know is what you have learned, but what you do not know is what you really are” - Farhelnissa Zeid

Last week I was fortunate enough to spend three days training down at Jing in Brighton participating in part two of the Advanced Myofascial Certificate. One of the places I consider 'home', at least in terms of bodywork training, being at Jing is always intense, challenging, tiring, wonderful and through-provoking. As such, I always come home and have to spend time processing what it is that I have learnt in my time there.

John F. Barnes was one of the first people to develop indirect myofascial techniques, and many people who now teach these techniques in the UK have trained with him. Indirect myofascial release is widely accepted as a powerful set of techniques which allow therapists to work more effectively with common pain conditions, emotional trauma and systemic conditions that do not respond to traditional massage approaches. Conditions such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, sciatica and whiplash are just some things that respond well to indirect techniques. These are all things in which I am interested, both as a practitioner who sees many clients with chronic pain conditions and as someone who has suffered from chronic pain in the past. Describing the techniques used in indirect work is difficult however, because so much of it happens only when the therapist is able to 'let go' and develop a listening touch. Developing this kind of touch takes time and practice.

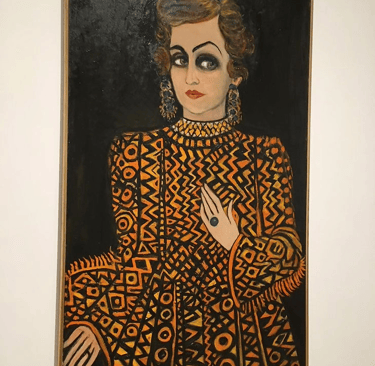

An unscheduled visit to the Tate gallery on Saturday morning got me thinking about the processes involved in learning and developing skills, and about the dichotomy that exists between what we learn and what we do, and indeed, what we think we know and what we think we do. As someone who has recently taken up drawing and painting I see many parallels between how artists work and how massage therapists work. One thing I did not understand about art until I started to do it is the amount of practice that it takes to master the techniques needed to create a piece of art. I think we are often blinkered in this respect because we generally see the finished masterpiece and not the many hours of work and practice that preceded it. We sometimes assume that artists are born with their skills and don't have to practice - the truth is that we can all be artists if we engage with the process of learning the techniques!

For an artist, exploring different techniques is what enables them to handle different mediums, see perspective, understand colour and composition etc., Practice is the key to learning, and it is an exploration that never really ends, with each phase of learning influencing our growth and development. I would argue, however, that techniques alone do not make art, because there is always something more profound in action when an artist creates a piece of art, that piece of art being reflection of their ability to draw on their own perceptions, ideas, and experience of the world around them.

Massage therapists work in much the same way, needing to learn and explore techniques, along with anatomy and physiology, in order to be able to practice what it is that we do. Our learning never really ends because humans are such mysterious and fascinating creatures - we know so little about how our bodies and minds work. When we first learn a new technique we often struggle to feel comfortable with it, we may meet tension in our own bodies (often caused by the effort involved in just doing said new technique) and our minds work overtime in an effort to understand what it is we are doing and how it might bring about a positive change for our client. We can get so wrapped up in this 'doing' and so attached to an outcome where positive change to takes place that we forget that what we are really doing: listening intently to our client and helping them to heal themselves through the medium of bodywork.

The paradox of bodywork, at least from the therapists perspective, is that we need to learn new techniques in order to be able to use them, but if we become attached to the techniques and forget about listening and responding to what we feel, we may find ourselves unable to give our client what it is they need. We end up 'doing' to the client rather than working with them. This is what I have taken away most from my three days training last week: that a 'listening touch' only comes with practice. It comes when we are able to hold a safe space for our clients, and when we are able to let go of technique to the point where we are simply responding to what we feel and experience.

I remember one of my teachers at Yogaview telling us that we would one day 'throw away all the techniques we had learnt and end up teaching from a place much deeper within ourselves, where the techniques were the foundation but not the place from which we did our work'. This is the place where magic happens!

45 Pickford Street, Macclesfield

07356 087628

Chronic Pain specialist, Holistic Bodywork, Holistic Sports Massage, Neurodivergent Massage, Hypermobility, Myofascial Release, Hot Stones, Deep Tissue Massage